AKMA 2 - OceanSenses 2022

Exploring extreme environment with a focus on science and education

.jpeg)

Firstly, we investigated and collected data from extreme environments such as cold seep sites. These sites are areas on the ocean floor where methane, hydrogen sulfide and other hydrocarbons naturally occur and bubble up in the water column. They are also sites where environmental stressors affect biological communities. Combining newly acquired data with the data already available to us will increase our ability to understand the present and predict the future.

Secondly, we wanted to develop a platform for interdisciplinary collaboration to bring AKMA science into the classroom. We aimed to develop different lesson plans to encourage discussion on the ocean and climate change among school pupils and learners of any age. We wanted to spread awareness about the Arctic environment and the potential impact of climate change on the biological communities that live there.

Scientists and educators from very different background have been working together and developed learning tools to experience the ocean using all our senses (touch, sight, smell, hearing and taste). The diversity within and between these smaller working groups is reflected in the variety of the resulting lesson plans which have been compiled into the OCEAN SENSES ACTIVITIES BOOK.

This expedition has received endorsement from the UN Ocean Decade, and a number of our objectives and goals aboard relate to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which are calls to action for all countries to ‘improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests’.

Here the Ocean Senses STORYMAPS.

CLICK here to watch the VIDEO REPORTAGE about Ocean Senses Expedition.

If you are interested to know more about this expedition, read the Cruise Report here and more BLOG POSTS below.

A Blog by Villads Holm - June 1, 2022

My name is Villads Dyrved Holm, and I am a master student in the Department of Geosciences at UiT, the Arctic University of Norway. My work on the AKMA2 expedition revolves around the study of foraminifera, single-celled organisms found in almost every part of the ocean. More specifically, my supervisors (Giuliana Panieri and Jan Pawlowski) and I are studying the foraminifera associated with methane seeps, where methane bubbles from the sea floor, creating a unique environment for life. A broader knowledge on these scarcely studied environments and their faunas is key to gaining a better understanding of how the release of methane affects, and has affected, different parts of the Earth system.

With an educational background rooted in palaeoclimatology -the study of past climates- I am used to the classical geological principle that the past is key to the present and future. If we understand how our planet has responded to past climate change, we can start to better predict future climate change. For my thesis work, however, this idea is turned around as we study present faunal response to methane release and compare it to reference sites not affected. Coupled with other disciplines such as geochemistry to quantify the methane release, this type of work might allow for better recognition of methane seepage episodes preserved in the rock record.

As I have previously only worked with fossilized foraminifera, the study of living specimens presents some unique challenges, but also great opportunity to learn. The arctic foraminiferal fauna hosts a wide variety of monothalamous specimens, single-chambered organisms not well-preserved in the fossil record due to their soft bodies. For me, this was a whole new world opening up, with many new species to learn.

For me, a normal day on the ship revolves around sampling and subsequent labwork. When the samples return to the surface, we stand ready in the geology lab. For my studies, my supervisors and I are only interested in the top 2 cm of the sediment sample, representing the very surface of the ocean floor with the shallow infaunal and benthic fauna. One scoop of sediment is preserved for future sequencing of environmental DNA, allowing for molecular studies of the faunas at different sites. The rest is sieved in different fractions for morphological identification where we basically identify these organisms based on their shape. Under a microscope, the specimens found to be still alive at the time of sampling are sorted from the rest. For the purpose of DNA extraction, we are mostly interested in living specimens, while the empty shells of dead organisms can be used for teaching purposes.

As a master student it is a humbling experience to be surrounded by all these experts in their individual fields, and I am trying to learn as much as possible while I am here.

Whenever there is some time off from the academical studies, I am doing my best to assist with the interdisciplinary OceanSenses project. I brought my banjo onboard, and am currently working on a children’s song, aimed at sparking the interest of foraminifera to the youngest school children, perhaps inspiring a new generation of foraminiferologists.

A blog by Solmaz Mohadjer and Mathew Stiller-Reeve - May 27, 2022

AKMA is about science, specifically understanding methane in the arctic. But AKMA is also very much about education. Throughout the AKMA project we have tried to develop new methods in science dialogues.

During the 2021 AKMA cruise we developed a project that we called POLARoid. In this project, some of the AKMA researchers communicated with a class each. The researcher and the students started hand-writing letters to each other. The students asked questions that the researchers answered before they went on the AKMA expedition to the Arctic. Once on board the research vessel, the researchers used Polaroid cameras to take a limited number of unique photos that they put in an album with descriptions. They sent these albums to the classes and followed-up by visiting the school, either in person or via zoom. We wanted to see how using “traditional” media could influence an interaction between students and scientists. The feedback was very positive, with one of the students saying “before this project I saw scientific life as something a lot distant from myself, but through this project I realized that it is not that far away.” This year, one of the other researchers on board -Sofia from Portugal- is re-creating this project with two classes. But we are also working other new ideas!

This year we wanted to extend the communication/education projects to include many more people on board. We also wanted to invite many more people from many different disciplines. Right now, there are teachers, a psychologist, an illustrationist, a videographer, law and gender scholars on board to work with the geoscientists to develop teaching materials about the AKMA research topics. The aim of the project is inspired by the SDGs and the UN Decade, who endorsed this expedition. We feel that people might think more about protecting the sea if they feel a connection with the seafloor itself; it’s an abstract place we can never visit. And if we cannot visit a place, then it might be challenging to feel a connection to that place. So we are developing teaching materials so pupils and students can “feel” the sea floor via their senses. We are developing tools inspired by the senses of sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste… One of the projects that integrates several senses to bring students closer to the sea floor is grounded in a paired teacher scheme.

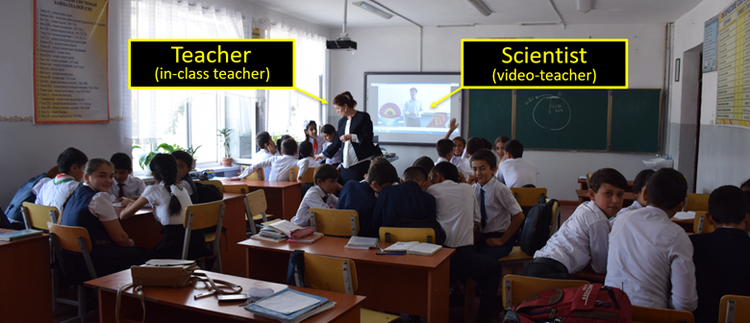

Paired teaching is an innovative technique that brings together teachers and scientists to collaborate, as equal partners, on developing and teaching lesson plans focused on topics that are relevant to teachers and their classrooms. The pedagogy is designed to support the teaching of scientific concepts by the lively video presence of a “guest scientist” and hands-on activities that are carried out in the classroom under the guidance of the “in-class teacher”. There are several educational resources for school teachers that incorporate the paired teaching technique, including the video library of MIT BLOSSOMS and ParsQuake.

During the 2022 AKMA-OceanSenses expedition, school teacher, Vibeke Aune, and geoscientist, Giuliana Panieri, created a lesson plan on a topic relevant to Vibeke’s classroom curriculum: methane and greenhouse effect. They filmed the lesson plan aboard the research vessel Kronprins Haakon with assistance from Solmaz Mohadjer, a geoscientist experienced with paired teaching, and Davide Oddone, a video reporter.

The video lesson introduces students to methane/gas hydrates, where they occur in nature, and why they matter. These topics are taught through lively discussions and observation-based exercises where students work together to study and related different datasets to discover processes that produce methane/gas hydrates.

The final educational package will contain a video lesson, a teacher’s guide and a lesson plan that can be printed and used by those who are interested in trying it out in their classrooms.

A blog by Katrin Losleben - May 27, 2022

Imagine a research vessel where lawyers, philosophers, sculptors, musicians, schoolteachers and scientists work together to study and teach about methane activity at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, a region vulnerable to climate change.

This is the AKMA2 expedition where we are currently testing what happens when we take advantage of our collective intelligence to tackle problems as complex as climate change and the health of our oceans and atmosphere. Our goal is to develop a better understanding of and a closer connection with hard-to-reach places like the seafloor in the Arctic Ocean and use that knowledge to bring people closer to extreme, yet fragile, environments.

We aim to go far, leaving no one behind.

Striving for true gender parity

No one should be left behind if we want to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Making progress towards gender equality and empowering all women and girls by 2030 (SDG 5) is especially critical. SDG 5 aims to eliminate the many causes of discrimination that women around the world face in both private and public spheres. Despite some progress in the last decades (e.g., more girls going to schools and more women serving in leadership positions), discriminatory laws and social norms remain pervasive.

Gender inequalities are still deep-rooted in all societies including here in Norway. Despite priding itself on being among the first countries to eliminate gender stereotypes and narrow the gender gap, women in Norway hold a 36.3% share of senior and leadership positions in the workplace. While men earn an average salary of 550,300 norwegian kroner, women earn just 382,000 norwegian kroner. The situation is grimmer for minority and indigenous women who are highly vulnerable to marginalization. This needs to change, not just in Norway, but in all societies. Otherwise, we run the risk of excluding half of the world’s population. That is half of our collective intelligence.

We often associated gender equality with women’s rights, but it is important to recognize all genders, including men. Without striving for true gender parity and eliminating harmful practices and discrimination at all levels for all genders, our progress towards the SDGs will be slow and halting.

Collective intelligence matters

Biological research shows that organisms who have more diverse ways of interacting with their environment are often more resilient to disturbances. Similarly, social science research shows the same for human communities.

Collective problems such as climate change require diverse ways of thinking and collective action. Think of fighting climate change as solving a large jigsaw puzzle. Now imagine people from different demographics and expertise have the pieces to this puzzle. Unless they come together and find out how their pieces fit together, the puzzle will remain incomplete. This means that climate change cannot be tackled by climate and environmental scientists alone. It cannot be solved by social scientists alone either. All datasets must be converged with other forms of knowledge, including indigenous knowledge, if we are to address climate change meaningfully.

Collective thinking and action also mean that we need to question how, why and for who we generate knowledge, and how we can integrate cognitive diversity into our ways of thinking and doing science:

· How do we gather knowledge?

· What counts as knowledge?

· Whose knowledge counts?

· What do we do with knowledge we gather?

· Who gains from the produced knowledge?

Asking these questions are as important as listening to those who can help us answer them. During the AKMA2 research expedition, we challenge ourselves to break down silos and build bridges with those we often don’t interact with. We sculp foraminifera with artists, write songs with musicians, develop games with school teachers, and make educational videos with scientists. Together we collect sediment cores, sieve samples in the lab and examine organisms under the microscope. We hope that our approach to collecting knowledge is inclusive, diverse and benefits all.

There is an African proverb that says “if you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” In AKMA2, we aim to go far so we will go together and welcome those who want to join the journey to the Arctic Ocean.

A Blog by Jessica Todd and Ciara Willis - May 25, 2022

Needless to say, Ciara and I have already started making a list of the other icebreaking vessel we hope to journey on one day. Top of the list, the new Australian Antarctic Iceabreaker, RSV Nuyina!, and the Canadian PC2 icebreaker!

A blog by Margherita Poto (with contribution of Juliana Hayden) - May 24, 2022

During our epic adventure, it is important that everyone aboard the research vessel speak the same language. Here are some important keywords to help us do just that.

G is for Governance

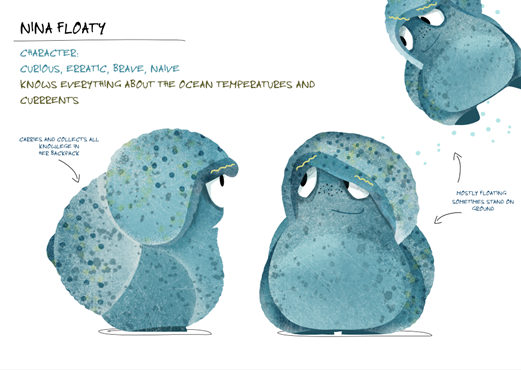

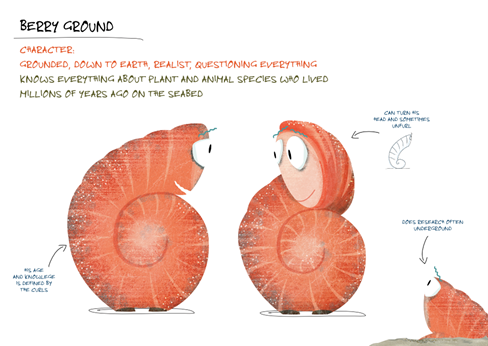

Did you know that the word ‘governance’ come from the Ancient Greek word κυβερνάω (kubernao) - which means to ‘steer the ship, to pilot’? Onboard the RV Kronprins Haakon, everyone shares their existing knowledge and steers towards creating knowledge. All the participants contribute with their lived experiences while also considering the rights of the environments we want to understand. On our expedition Nina and Berry, our new ambassadors, will help us dive into the Story About Knowledge (A Story About Knowledge. Illustrated version. ECOCARE) to learn about the importance of sharing information and how to participate in environmental science policy and protection (SECURE).

A is for Animals

Our crew is composed of both human and non-human beings. Our special team of animals represents the key qualities necessary for both knowledge sharing and co-creation.

-

wise leadership - Brave Bear

-

strength and resilience - Mama Eagle

-

adaptation, flexibility and boundary transcension - Dancing Salmon

-

humility and self-reflection - Loving Mole

-

Networking and fostering partnerships - Bouncy Ragnetta

This team of extradordinary animals will tell the stories of AKMA2 OceanSenses expedition and the research onboard - to students, teachers, and researchers around the world. These intrepid animals will cross oceans to share their experiences at sea in the Arctic, first stop Mato Grosso, Brazil to visit the Chiquitano indigenous villages (aldeias). They will also travel to Tanzania’s Ruvuma region. Children around the world will work in tandem with ECOCARE’s expansive network of indigenous scholars, teachers and university professors to learn about our beautiful planet, the oceans and the importance of caring for the environment. Students will be asked to develop stories and illustrations that draw connections between the world of deep sea research to their own experiences.

Bobbelur Gå-på-Tur (the smart Bobb with a talent for travel and exploration) will also join our expedition. Bobbelur, the seashell symbol of the SECURE project represents the aims of Agenda 2030, in particular, SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well Being), SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 14 (Life Below Water). Bobbelur connects scientists from the SECURE project who investigate the nutritional, medical and environmental properties of the low trophic marine species.

B is for our smiling Blue Planet

The ECOCARE logo, Our Smiling Earth (La Nostra Terra Sorridente) embraces people, continents, waters, and hearts. She is super excited about her journey on the Kronprins Haakon, enabling her to connect blue spaces and people around the world through an empathic, compassionate, and caring lens, all thanks to the AKMA 2 OceanSenses team!

A blog by Mari Heggernes Eilertsen - May 24, 2022

Hydrothermal vents and cold seeps have many things in common, both habitats have an abundance of energy-rich chemical compounds flowing out of the seafloor, such as methane and hydrogen sulphide. These compounds are food for bacteria that perform chemosynthesis – the dark cousin of the better known photosynthesis – where instead of using light as an energy source, the deep sea microbes can use chemical energy.

Chemosynthetic bacteria can grow freely on surfaces, or they can be harnessed by animals who keep the bacteria inside their bodies as symbionts, and get nutrients from them. One important symbiont-hosting animal in vents and seeps in the Arctic are tubeworms, which can form very dense patches. Think of the free-living chemosythetic microbes like grass, and the tubeworms as trees - just like on land animals graze on grass and hide or shelter amongst the trees in a forest. In the deep sea, animals graze on bacterial mats and use the tubeworm forests as trees in which to shelter.

Through chemosynthesis, vents and seeps offer an abundance of food, in an otherwise food-deprived deep sea. However, to take advantage of this food source, the organisms living here have to tolerate extreme environmental conditions. Hydrogen sulphide, which is one of the chemicals that can be used for chemosynthesis, is also toxic for animals that do not have special adaptations to tolerate it.

Although vents and seeps are sister habitats, there are some important differences, for example that hydrothermal vent fluids are hot, while seep fluids have the same temperature as the seawater around. Hydrothermal vents are usually found along mid ocean ridges (underwater mountain chains where the continental plates meet), with rocky and hard substrates, while seeps are found on continental margins in soft sediments. The animals found in vents and seeps often belong to the same groups (families and genera), but rarely the same species are found in both vents and seeps.

In the Arctic, vents and seeps are found in close geographic proximity, and even though the vents are placed on the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge, they have sedimented areas that may be more similar to seeps. Therefore, this area is particularly interesting for studying the connection between vent and seep faunas, and the potential overlap in species.

This is one of the questions we aim to answer with the project “Vent & Seep fauna in Norwegian waters”, funded by Artsdatabanken. The project is a collaboration between the Center for Deep Sea Research and the University Museum at the University of Bergen, and the CAGE center for excellent research at the University of Tromsø, along with several other national and international collaborators. The Center for Deep Sea Research has been performing multidisciplinary research on hydrothermal vents along the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge for more than a decade, and through the collaboration with CAGE and the AKMA project we benefit from their expertise on Arctic methane seeps to better understand the connections between these extreme deep-sea ecosystems.

A blog by Jane Zimmerman - May 21, 2021

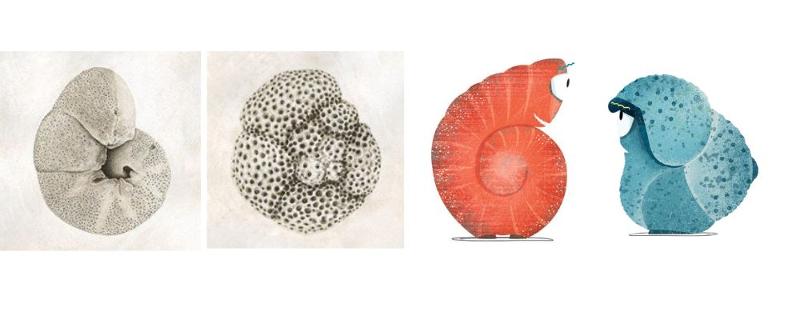

Giuliana and Jane share a passion for small creatures. On the AKMA 2 OceanSenses expedition, they are exploring foraminifera together. Foraminifera are tiny, single cell organisms that live in every ocean and sea on our planet. With the help of foraminifera, micropaleontologists like Giuliana can study the history of planet Earth, its climate and natural processes that occurred millions of years ago.

.jpg)

Giuliana has been fascinated and in love with foraminifera for many years now and has always wanted to share this with people, especially children around the world. The vast majority of foraminifera are extremely small, ranging in size from 100 μm to 1 mm in length. They are the most abundant single cell organism in our oceans, and despite their small size they are actually crucial for understanding the evolution of life and the environment on Earth. Unfortunately the general public doesn’t know much about foraminifera nor their significant role in Earth history.

This is where meeting Jane proved a unique opportunity. Jane is an illustrator, artist and graphic designer with a deep love for the many small creatures that populate our planet - those we don’t often see and don’t know much about. Giuliana and Jane bonded immediately over their passion for small creatures and jumped into a fun adventure to create Nina and Berry. Nina and Berry are two foraminifera who will guide us on a dive into the wonderful world of foraminifera living in the Arctic Ocean.

Both Nina and Berry have personalities which are based on what we know about foraminifera today thanks to micropaleontology.

Nina Floaty is based on the foaminifera species Neogloboquadrina pachyderma, which is a foraminifera that floats in the ocean.

Berry Ground is based on the foraminifera species Melonis barleeanus. Melonis barleeanus is a benthic species - meaning they live in or on the seafloor.

Giuliana’s niece Cecilia immediately fell in love with Nina and Berry and Cecilia was actually the one to name them. Since then, many kids (and adults!) have been charmed by these two and the stories they have to tell. The smile that these characters put on people’s faces seems a perfect bridge to bring the unknown but fascinating world of foraminifera closer to people and inspire them to protect our precious Earth along with all the wonderful beings that populate it.

.jpg)

Achievements:

• Nina & Berry have been printed on t-shirt in Matirima, Tanzania, the students are “wearing” the science that Nina & Berry will teach them. In the meantime, Anna is making baskets to contain Nina & Berry 3D models

• Giuliana gave a presentation on Nina & Berry to the Environmental humanities group at UiT

• Nina & Berry joined the AKMA2/Ocean Senses expedition on board of the RV Kronprins Håkon

A blog by Kate Waghorn - May 19, 2022

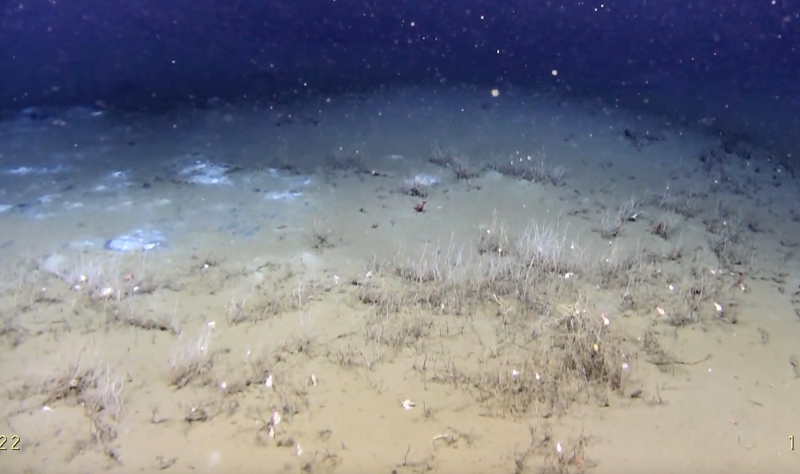

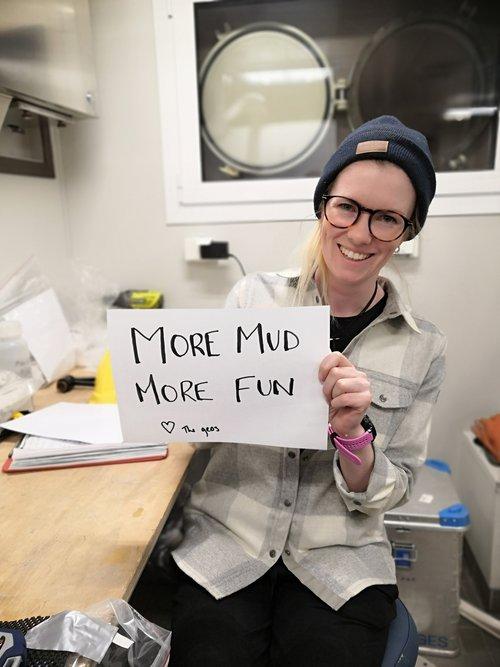

Around 8 years ago I moved from New Zealand to Norway to study methane in the Arctic. My friends thought I was nuts. They still might be right, I haven’t decided yet. Anyway, to cut a long story short about this time 8 years ago I was on my first expedition with UiT. Not my first expedition on a ship but my first in the Arctic. And how ready I was for my great Arctic Adventure! I will be the first to admit that this particular Arctic Adventure wasn’t exactly what I had in mind. I already had trouble sleeping due to a combination of jet lag and the very jarring introduction to the midnight sun but then I was introduced to the Chirp. The Chirp is a instrument which basically beeps. Those beeps carry to the seafloor and actually the sound penetrates a ways into the subsurface. But the beeps… every 2 seconds the Chirp chirped. And every 2 seconds my eyes flew open again. The chirp will have a home in a ‘Torture devices of History’ museum one day. I was trying my best to keep my spirits up, after all it was all new and exciting and I was on an epic adventure doing my PhD in this Arctic paradise (smelly research vessels can also be Arctic paradises in the right circumstances, I promise). But then, we arrived at my study site - the site I would devote my next four years to understanding and knowing as intimately as anything or anyone in my life - and …. there was nothing. To quote a colleague it was the most boring seafloor that had ever existed. My heart sank.

I don’t want this to go on too long and writing this down was already somewhat emotional for me. AKMA2 might well be my last trip into the Arctic so I was thinking a lot about what got me here. How and why I ended up studying this area with ‘the most boring seafloor that ever existed’ for 8 years of my life. And for most of that time, it was the ‘most boring seafloor’ site. You see, dear reader, it turns out it is actually really hard to find the exciting bits of the seafloor. Literally, it is like finding a needle in a haystack. But last year we actually found that needle and all of a sudden the most boring seafloor that had ever existed became exciting. I cannot imagine there will be too many more experiences that are as gratifying and validating as that. Even if the site had remained ‘boring’ I felt a strange connectedness to this little lump of rock and sediment in the middle of the ocean. I think that is what people mean when they talk about topics like climate action - the concept that we have to connect to something in order to feel driven to action. Well, over the years I certainly connected with the site.

The site is actually called the Svyatogor Ridge. I have written a bit about it in general in the study sites section of the website so I won’t repeat that here. Just today I saw a picture of some worms (I won’t get too scientific about them, if only because I can’t) that are living in this study area and even if they are weird little aliens with baboon butts I was awestruck. We didn’t see these critters the first time we came to this site with the ROV and I am sure next time we will see something new again. And I have to wonder, how many more utterly amazing things are out there, waiting for the right person to devote far too long to a single patch of the seafloor. Whether or not the Svyatogor Ridge was an actual oasis in the cold dark of the Arctic depths, it was always going to be extremely special to me but I am so glad there are now more people around me just as excited about the site. Even more so, I feel a sense of joy that this site exists as a little home for all sorts of critters of the deep but it’s a bittersweet feeling because I do have to wonder whether habitats like this will survive long enough to evoke wonder in future scientists.

![received_349559177274740[1].jpeg](/Content/812497/transformation=scale10000x800/received_349559177274740[1].jpeg)

For that reason, I wanted to be a part of the AKMA project and expeditions. At minimum I can share my weird attachment to the Svyatogor Ridge with others but ideally I can make small changes towards the way we view our planet and maybe be part of a change that protects habitats like the one on the Svyatogor Ridge for the future.

A blog by Monica Clerici - May 19, 2022

You might wonder why exactly a psychologist would join a geoscience oriented research expedition in the Arctic. I am a PhD student from the University of Milano-Bicocca and I am currently studying how immersive technology can bring people closer to sustainability issues. I am part of the MiBTec advanced laboratory, which aims at understanding the relationship between the human mind and virtual, augmented and mixed reality. I was invited to join OceanSenses because I am particularly interested in sustainability and innovative educational tools.

During the first months of my PhD we developed and tested Virtual Reality multi-sensory applications whose aims were to transmit complex scientific concepts to everyday people. From understanding the biodiversity and importance of corals, experiencing what environmental scientists do in the field, to feeling the beauty of the ocean.

With a network of humanists, engineers, technicians and environmental scientists the aim of our lab is to produce immersive experiences through which it’s possible to study the human mind- in my case, specifically nature connectedness and pro-environmental behaviors.

During OceanSenses, I have been a part of an exceedingly interdisciplinary group - a melting pot of knowledge. From biologists and geologists to musicians, teachers and more. I have had the opportunity to grow, both personally and professionally and my life aboard the research vessel has been filled with adventures from the start. There have been many discussions and debates but it has been clear from the start that the environment is caring, and sharing. Any fears I had before embarking left somewhere between the first cake-time and workshop.

Above all, this journey was framed by the breathtaking experience of being in the middle of the Arctic, seeing the depth of the ocean and the activity on the seafloor, being surrounded by sea ice and even walking on it! One of the things that I am most grateful for is the availability and constant guidance of the scientists that have helped us to understand everything that was happening on board. Thanks AKMA project for having me and I look forward to continuing this amazing collaboration

A blog by Fulvio Franchi - May 16, 2022

If we want to leave the ship and venture onto pack ice, the ice has to be super solid. So, if we want to take samples of the sea ice we have to find the right thickness of ice and also the right kind of ice - the ice shouldn’t crack when the hull of the ship cuts through it. So after a few hours of sailing across very thin ice we finally reached a place where we could sample the sea ice.

We were almost at 80° N when the captain gave us the green light. We donned our special water tight clothing and grabbed the ice corer. The first people to leave the vessel were the polar bear guards - one carries a gun while the other scouts the ice and reports back to the vessel. Having a rifle with us is necessary for work on the sea ice because we cannot risk an an attack by a polar bear. But, no bears have yet come near during our sampling so our safety measures work. The rest of the team back on the vessel were on deck, scouting the horizon with binoculars for polar bears.

The first step on the Arctic sea ice is one of the strongest experiences I had in my life. The white of the snow and ice stretches all the way to the horizon and it is so incredibly bright. We were literally walking on the surface of the ocean, underneath our feet was hundreds of meters of freezing cold ocean and only a few meters of relatively thin ice separating us from the abyss.

Coring ice is quite straightforward - a 1 m long barrel (14 cm diameter) powered by a hand drill bites into the ice. The total length of the core is 1.3 m but we collected 4 cores to ensure we have enough ice to work with when we get back to shore. We had to quickly pack the ice cores and transfer them to a cold room on the research vessel where the cores will be sliced, vacuum packed and sent off to laboratories around the world.

They are just at the beginning of their new journey with us.

A blog by Filip Maric - May 14, 2022

With the rapid growth of fields like EcoHealth, planetary health and sustainable healthcare we are increasingly learning about the complex ways in which human health depends on our planetary ecosystem. For the most part, planetary health research and subsequent considerations about relevant interventions are directed at environmental phenomena that impact human health fairly directly. Air pollution and even climate change, for example, kind of ‘happen’ on the surface of the Earth and have some relatively immediate effects on human health. One exemplary intervention is therefore to consider the potential of active transport as a way to reduce urban air pollution caused through other forms of transport that generate significantly larger amounts of air pollution.

But what happens when things are much much further away, and quite of out of reach like at the bottom of the Arctic Sea? As a healthcare professional thinking and working in planetary health, I’m fascinated by questions that pop-up when you start thinking about this. How does the ‘health’ of the Ocean floor, its ecosystems and biodiversity (SDG14) relate to the health of life on land (SDG15), including good health and wellbeing for humans (SDG3)? What does it mean to do planetary health in relation to the ocean floor? And whose health will we have in focus? Will it always just remain the health of humans that populate the surface of our planet? Or will we also more actively care for the health of foraminifera, nematodes, coccolithophores and other such wonderful beings that populate the seas of the earth and about which most of us have never even heard, even though they have animated and shaped our planet for millions and millions of years?

I’m not so naïve to think that I will come to conclusive answers to any of these questions any time soon. But taking part in the AKMA 2 OceanSenses cruise is an exceptional opportunity to dive into this wonderful, and wonderfully unknown world and, at the very least, wonder what planetary health could be if we thought it in ever more inclusive ways, expanding SDG3 to really be about health and wellbeing for all, including those in the depths of the sea.

A blog by Andre Jensen - May 14, 2022

On the far NW Svalbard shelf, bordering the Arctic Ocean in an often completely ice covered area many strong gas seeps sit bubbling away on the seafloor. Using subsurface imaging methods, we see that the case is migrating up through large fault zones and subsurface structures. As this area is covered by ice for a lot of the year it can be difficult to study what is happening at the seafloor - but seeps are important sources of carbon into the ocean so it is also important for scientists to understand the where, why and how of these Arctic methane sources.

.jpeg)

We used the ROV to investigate this area and with this new data we can hopefully get a better idea of the geological processes at play as well as the environment surrounding them.

A blog by Jane Zimmerman - May 13, 2022

Today, we learned a little bit about sculpting. Jane Zimmerman, an artist, illustrator and designer is aboard the research vessel with us and she was able to teach us how to use modelling clay to make models of… science things. Mostly, sculptures of foraminifera. Foraminifera are teeny tiny, usually less than a millimeter in length. But foraminifera are very important for creatures so small as they can tell us a lot about the evolution of life and about environmental conditions far back in time. It can be difficult to truly understand something that you cannot see with your own eyes but we really need to be able to intimately understand Foraminifera. Using modelling clay, we were able to make enlarged foraminifera that we could pick up, see, feel and turn around in our hands. Our sense of touch brought us closer to foraminifera.